Education: March 2018 Archives

Last week the Oklahoma House approved HJR 1050 by a bare majority of 51 votes, pushed by the Chambercrat House Leadership, voting to erode the constitutional protection against tax increases without approval of the voting public. These 51 representatives, including two, Leslie Osborn and Glen Mulready, who are seeking higher office, voted to make it easier for politicians at the State Capitol to pass tax hikes without asking for voter approval. I'm embarrassed to see on the list of traitors to the taxpayers the names of legislators that I have endorsed and defended in the past.

Mainstream news coverage of Oklahoma's budget battle has given many voters the mistaken impression that a 75% legislative super-majority is the only constitutionally permissible way to raise taxes. When I corrected someone who made that assertion, I was told that I was absolutely wrong.

Article 5, Section 33, of the Oklahoma Constitution is best known by the initiative that enacted it: State Question 640. Here is the language:

§ 33. Revenue bills - Origination - Amendment - Limitations on passage - Effective date - Submission to voters.A. All bills for raising revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives. The Senate may propose amendments to revenue bills.

B. No revenue bill shall be passed during the five last days of the session.

C. Any revenue bill originating in the House of Representatives shall not become effective until it has been referred to the people of the state at the next general election held throughout the state and shall become effective and be in force when it has been approved by a majority of the votes cast on the measure at such election and not otherwise, except as otherwise provided in subsection D of this section.

D. Any revenue bill originating in the House of Representatives may become law without being submitted to a vote of the people of the state if such bill receives the approval of three-fourths (3/4) of the membership of the House of Representatives and three-fourths (3/4) of the membership of the Senate and is submitted to the Governor for appropriate action. Any such revenue bill shall not be subject to the emergency measure provision authorized in Section 58 of this Article and shall not become effective and be in force until ninety days after it has been approved by the Legislature, and acted on by the Governor.

Sections A and B apply to all revenue-raising bills. Section A echoes the Federal Constitutional requirement that revenue bills originate in the legislative chamber closest to the people. The normal path for measures raising revenue is described in Section C: Approved through the normal legislative process, then ratified by a vote of the people at the next general election.

Section D is intended for true emergencies, unforeseeable circumstances, like a natural disaster. The threshold is high enough to require agreement from every reasonable legislator, but not so high that a stubborn handful can block the measure in a true emergency.

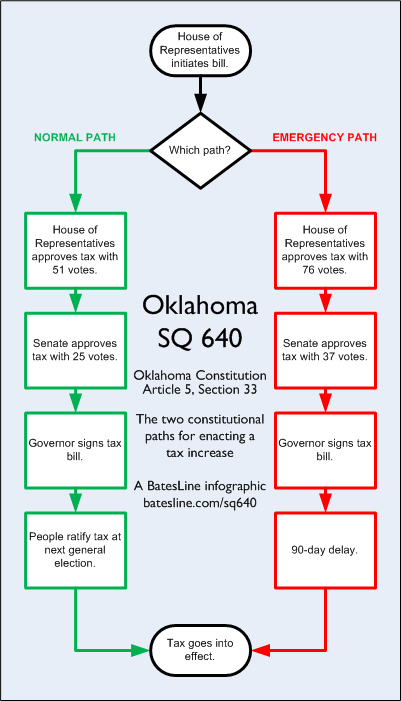

For those of you more visually inclined, here's a flow chart:

The movement to limit the legislature's power to impose taxes was a reaction to HB 1017, the largest tax increase in Oklahoma history, enacted on April 19, 1990, by the legislature, without a vote of the people. At the time, Democrats had supermajorities in both houses of the legislature.

According to a story in the April 20, 1990, Daily Oklahoman, Corporate tax rates were increased by 20%, sales tax rates by 12.5%, and personal income tax rates by between 1.2% to 16%, depending on income level. Schools were required to meet accreditation standards, teachers' minimum salary scales were increased, maximum class sizes were lowered, and money was allocated to fund voluntary school consolidation for up to 250 of the state's then-604 school districts. (28 years later, Oklahoma still has 522 school districts.) News stories after HB 1017 went into effect report complaints from teachers and administrators that the extra money was appreciated, but the strings attached were making it hard to use the money wisely.

HB 1017 was approved in the wake of a week-long teachers' strike of questionable legality that began on April 16, 1990, called by the Oklahoma Education Association after an education funding bill failed to pass with an emergency clause for immediate effect. The strike was supported by a number of school districts.

Many Oklahomans felt that their elected officials caved to pressure from the teachers' union, ignoring the economic impact of higher taxes on the general public. Dan Brown, leader of Stop New Taxes, the movement opposing HB 1017's tax increases, described the reaction for the April 25, 1990, Daily Oklahoman:

These calls have been from retirees, teachers and administrators, small town newspaper editors and representatives of small and large businesses who feel betrayed by the Legislature and the governor, Brown said."In general, they fear the trend of government decisions being made by mob rule,'' he said. "They have lost their faith in our system and their belief that anyone at the Capitol hears them.''

While some opponents of higher taxes wanted to attempt an immediate repeal, the principal anti-tax organization at the time, Stop New Taxes focused on an initiative petition to restrict the legislature's ability to raise taxes without the direct assent of the taxpayers. In the early stages of the effort, Dan Brown described the intent:

"The taxes we plan to include in this petition include taxes on sales, personal and corporate income, ad valorem, service, etc.,'' Brown said. "We are not planning to include limitations on fees in this amendment.''He said the group is considering adding a provision that would allow the government to obtain money in emergencies, such as a severe prison riot or economic depression.

(An initiative petition to repeal the HB 1017 taxes, but which also added a variety of other reforms, did reach the ballot but not until November 1991, after the bill had already been in effect for a year, fell short, but nevertheless won 45.7% of the vote. Here is a timeline of events leading up to passage of HB 1017 and the attempt to repeal it.)

The heart of what became SQ 640 is this: At the State Capitol, it's easy for a legislator to forget where he came from and who he works for. He is surrounded by special pleaders for special interests. He finds himself becoming assimilated into the capitol subculture, developing an "us vs. them" mentality, where "us" consists of fellow legislators and the lobbyists that pretend to be his friends, and "them" consists of the rowdy, rude, ignorant electorate who got them into office and stupidly expects them to live up to their campaign rhetoric. The bureaucrats and lobbyists and legislative leaders tell him, and he begins to believe, that the Capitol endows its denizens with special knowledge that his constituents lack. His fellow Capitolines speak nicely to him, tell him what a couragous and brilliant man he is, admire him for growing in office, assure him that his betrayal of his campaign promises is just and wise. His betrayed campaign volunteers and constituents speak angrily to him, driving him further into the arms of his new love. The seed of legislative infidelity finds fertile soil.

The phenomenon of concentrated benefit trumping diffuse cost, explained by public choice theory, only compounds the problem: Advocates who are protecting or demanding a concentrated benefit will be better organized, more present, more passionate than the diffuse mass that will bear the cost. To the weak-kneed legislator, the demonstration on the Capitol steps will appear to be a bigger and more important political force than their constituents. Call it the puffer-fish effect: An organization making itself look bigger than it is for the purpose of intimidation. (The Federal Essential Air Service program is one instance of the phenomenon; pollution provides a non-economic example.)

This problem of alienation of legislative affection has been mitigated somewhat by several reforms: Legislative term limits that prevent legislators from making the Capitol a career and limit concentration of power through seniority, limits on the legislative calendar (February through May, Monday through Thursday) that allow a legislator to spend more time back home among his constituents, and SQ 640, which prevents taxes being enacted hastily in response to pressure from those who would benefit from the tax increase. Either there has to be a near-universally acknowledged emergency, or there will be a cooling-off period in which tax advocates have to persuade the general electorate that a tax increase is necessary.

Over 230,000 signatures were gathered on an initiative petition to put SQ 640 on the ballot. While the proponents had wanted the issue on a general election ballot, Democrat Gov. David Walters scheduled it for March 10, 1992, perhaps hoping that special interest groups would be able to turn out their voters to defeat it. Even so, Oklahoma voters approved SQ 640 by a significant margin: 373,143 to 290,978, 56.2% to 43.8%.

Since its passage, a number revenue increases have gone into effect. In a column from earlier this year, OCPA President Jonathan Small listed several within the last decade:

As you might expect, some lawmakers are now looking to wage war against 640. They claim it confines government by making any revenue-raising measures impossible to pass. But that's not true.In 2009, 2010, and 2011, legislators organized bipartisan supermajorities to pass bills that raised some $224 million in new annual state funds and $268 million in annual matching federal dollars.

Press releases from the executive branch, Board of Equalization reports, and legislative budget summaries show that the 2015, 2016, and 2017 legislative sessions combined to annually increase revenue for appropriation by more than $500 million.

Moreover, Oklahoma has raised personal income tax rates, cigarette taxes, gaming taxes, and authorized a state lottery (a tax on the poor) since 640 was adopted by voters.

So mostly during Republican majority control, annually recurring revenues were raised more than $724.7 million.

HB 1017 was something of a pyrrhic victory for public-employee unions and their Democratic allies in the legislature. It provoked a taxpayer revolt that resulted in passage of term limits that fall, followed in 1992 by SQ 640. Democratic supermajorities gave way to Republican supermajorities and a sweep of statewide elective offices. Statewide initiatives to raise taxes for education have been defeated overwhelmingly -- SQ 744 in 2010, 19% to 81%; SQ 779 in 2016, 41% to 59% -- which may explain why our weasely state reps thought they need to make it easier to raise our taxes without asking our permission.

The teachers' union and their allies seem intent on blocking any improvement for teachers that doesn't also kill or cripple SQ 640 and raise taxes permanently. The fact that a decent increase in minimum teachers' salaries could be funded without raising taxes seems to have inspired them to double their demands and expand them beyond the classroom to include state bureaucrats. As in 1990, they may succeed in intimidating a majority in the legislature to do their bidding, but as in 1990, their victory may lead to long-lasting damage to their political clout.

As passionate as many Oklahomans are about their local public schools, particularly in small towns where the school system is about the only thing keeping the town from dying, an increasing number feel alienated from public education. They see a system mired in the latest educational fads, entranced by political correctness, discarding tried-and-true for novel and trendy, and sometimes directly hostile to the values they believe should undergird education. They see problems that no amount of money can fix; accelerating down the wrong track will never get the train to its destination. The good will Oklahomans have toward teachers may not extend to the beneficiaries of the OEA's other demands, and it may not even extend to giving teachers a much greater raise than most Oklahoma taxpayers have received over the last decade.

A significant number of the 35% of Tulsa Public Schools who left the district in the last two years did not head to greener pastures out-of-state, but to other Oklahoma school districts with comparable pay, according to an investigation led by Tulsa World education reporter Andrea Eger. Teachers interviewed for the story cited poor leadership and lack of respect from administrators at district and school level as the main reason for seeking a new place of employment.

I encourage you to read the article at the World's website, but here's a summary to give you a sense:

Teachers mentioned overly prescriptive curricula that had them reading from a script or coordinating laptop-based instruction, reducing the teacher from a creative instructor to a mere "computer lab attendant" and making it impossible for teachers to learn and respond to the individual struggles of their students.

One veteran foreign language teacher quit to take a lower-paying gig as a freelance photographer: ""It was 100 percent the awful administration and the district showing us they didn't care."

Discipline, or the mandatory lack thereof, seems to have significantly damaged teacher morale and inspired departures and early retirements. Robert Dumas, a former Memorial Jr. High teacher criticized the all-positive, all-the-time news from district headquarters, saying, "Our suspensions are down because they stopped suspending kids for the same things." Mike McGuire, now retired from East Central High, suggested that the state aid formula, which is based on average daily attendance, might be a motivation for reducing the number of suspensions.

Mr. McGuire then dropped this bombshell, which (I hope) will get an investigation of its own (emphasis added):

McGuire said his tipping point was being formally reprimanded for how he responded to students concerned about two of their classmates being allowed to return to school after 10 days in jail on human trafficking complaints."I told my students, especially the girls, 'If you're concerned, you need to tell your parents so they can express their concern to their school board representative,' " McGuire said. "If my daughters were going to school in a place with pimps running around it, I would want to know."

Apparently the paramount value for Tulsa Public Schools administration is making the administration look good. It's not a problem to have pimps in school; it is a problem to let parents know so they can take action to protect their children.

(This reminds me of the time, in 2000, that I got scolded by Jeannie McDaniel, then head of the Mayor's Office for Neighborhoods for Susan Savage, for alerting Crosbie Heights neighborhood leaders to a plan to demolish half of it for an amusement park. McDaniel didn't seem to be bothered that influential people intended to destroy the neighborhood, but that neighborhood leaders were panicked because they'd been told about it.)

Hats off to the Tulsa World reporters who produced this investigation and to the editors who gave it the green light. At a time when it's common wisdom to blame every school problem on the amount of state aid (and Superintendent Deborah Gist tried that gambit in this story), it would have been easy to bury the story for the sake of maintaining that narrative or out of fear that the story would provide fodder for the "wrong" people.

Meanwhile Deborah Gist is focused like a laser on the important issue of schools wrongly named after honorable and heroic men of history like Christopher Columbus and Robert E. Lee.

Just remember, folks: The TPS preliminary expenditure budget for 2017-2018 was $561,241,887 for an average daily membership for the first nine weeks of the year of 37054.40. That's $15,146.43 per student.

MORE: One of the teachers interviewed for the story mentioned a "student behavior management system" called "No-Nonsense Nurturing," which, combined with very scripted curriculum, became "too much to bear." On Twitter, Abigail Prescott links to an essay by a teacher explaining the No-Nonsense Nurturing system, which evidently involves coaches in the back of the classroom giving commands to the teacher through an earpiece, which she is supposed to carry out in a monotone. The World story quotes Superintendent Gist as saying that "TPS is committed to the philosophy that suspending students isn't a real solution to underlying behavior issues and noted that it offered the new behavior management strategy called 'No Nonsense Nurturing' only in response to personal concerns expressed to her by teachers when she first arrived in summer 2015."