Tulsa, May 1921: Moescha Rosenberg sues Sinclair

As we approach the centennial commemoration of the Tulsa Race Massacre at the end of this month, I was curious to look through contemporaneous records to learn more about the times in which it occurred.

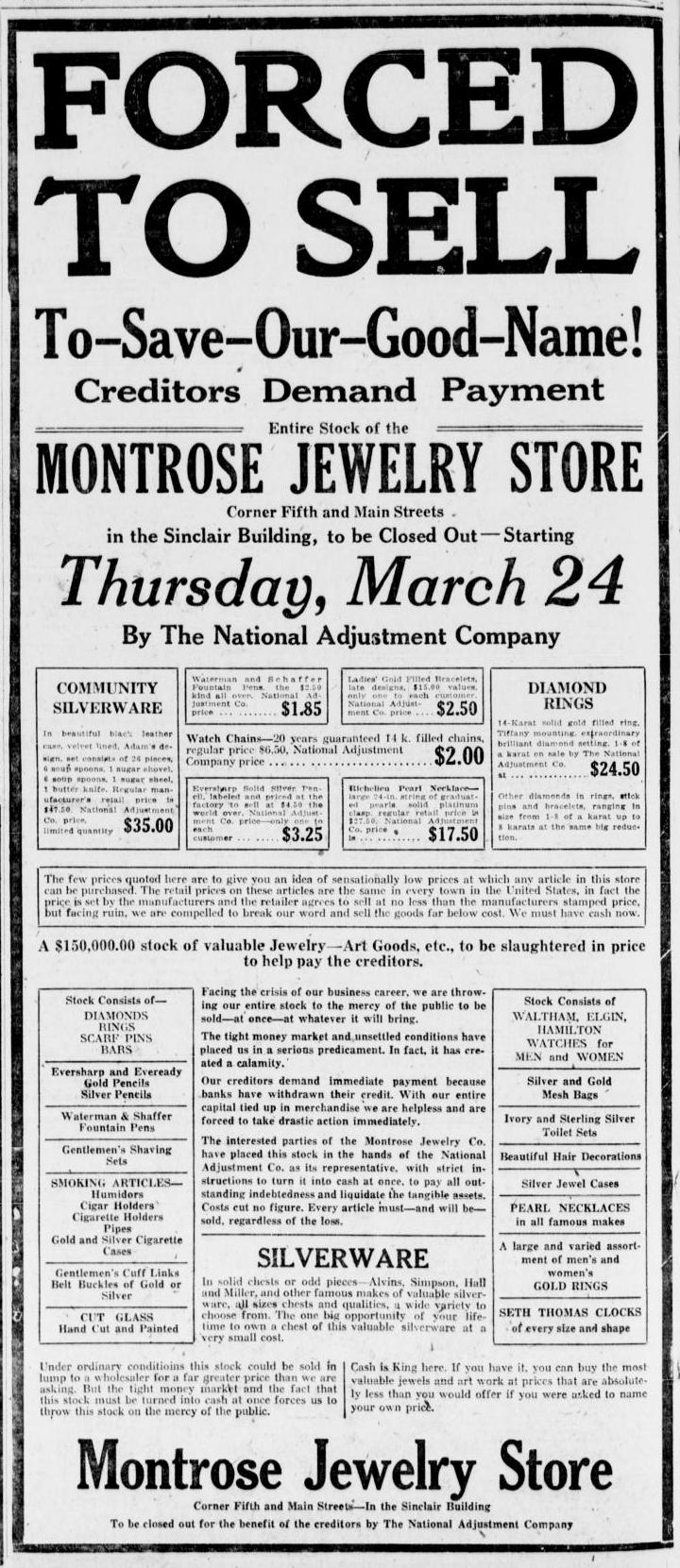

On page 6 of the May 1, 1921, edition of the Tulsa Sunday World, there's a story about a $473,600 lawsuit brought by jewelry store owner Moescha Rosenberg against Sinclair Oil and Gas, owners of the building in which his store was located. On March 15, 1918, Rosenberg entered into a 10-year-lease for retail space on the northwest corner of the building, sitting right on the highly visible southeast corner of 5th and Main in downtown Tulsa, at the junction of two streetcar lines. His rent was $400 a month. According to 1919 and 1921 city directories, the shop was called Montrose Jewelry Company, located at 2 East 5th Street. Ads for the store, sometimes called "Montrose of New York" or "The Montrose Shop," appeared often in the papers, particularly in the run-up to Christmas.

On page 6 of the May 1, 1921, edition of the Tulsa Sunday World, there's a story about a $473,600 lawsuit brought by jewelry store owner Moescha Rosenberg against Sinclair Oil and Gas, owners of the building in which his store was located. On March 15, 1918, Rosenberg entered into a 10-year-lease for retail space on the northwest corner of the building, sitting right on the highly visible southeast corner of 5th and Main in downtown Tulsa, at the junction of two streetcar lines. His rent was $400 a month. According to 1919 and 1921 city directories, the shop was called Montrose Jewelry Company, located at 2 East 5th Street. Ads for the store, sometimes called "Montrose of New York" or "The Montrose Shop," appeared often in the papers, particularly in the run-up to Christmas.

According to Rosenberg, not long after he leased the space, Sinclair employees began harassing him to get him to leave. First, a company official, C. E. Crawley, "offered to buy his stock if he would give up his lease. When he refused he says that the company made threats to add two stories to the building and permanently close up the entrance which he was using." Then Sinclair employees cut the lights to the store at night, and he lost his insurance policy, which required the lights to be on all night, and that forced him to operate without insurance. After an automobile crashed into the shop window, Sinclair boarded it up and refused to replace it with new glass, and refused to let him put in "sectional glass." When Rosenberg put a sign on the boards saying that he was still open for business, the building superintendent tore it down. When Rosenberg hired two clerks to work for him, Sinclair claimed that he was subletting the space in violation of his lease and sought a court order to evict him; Rosenberg got an injunction to get the company to leave him alone. Finally, about two months earlier (late March 1921), he gave up, dismantled his store fixtures (worth $16,000), liquidated his stock at a loss of $75,000, and then vacated with seven years remaining on his lease. Rosenberg's lawsuit demand for compensation included his estimated $50,000 per year income on the remainder of his lease. Rosenberg claimed that the space would now have a rent of $2,000 per month. (The city directory for the following year, 1922, shows the Suzanne Shop, milliners, in the space at 2 East 5th.)

The situation has the appearance of a landlord trying to force out a tenant in hopes of either charging higher rents or providing a prime location to a better-connected tenant or both.

Rosenberg's case went all the way to the Oklahoma Supreme Court. The details of the case are not available online, and the ruling is terse, but it appears that Rosenberg prevailed in District Court, Sinclair appealed to the Supreme Court, and Rosenberg failed to file an answer to the appeal. The Supreme Court reversed the trial court and remanded the case "with directions to sustain [Sinclair's] demurrer to the petition." I was unable to find a newspaper story on the final disposition, but it appears that Rosenberg's cause was lost. The case has an entry in Pacific Reporter, Vol. 219, p. 650.

Moescha Rosenberg seems to have been quite a flamboyant businessman. When he was ready to close his shop in Glen Cove, Long Island, in preparation for a move to Tulsa, he placed an ad in the local paper threatening to publish the names of all the customers who had outstanding debts with the store. The story hit the wire services and was published all over the country. From the Long Beach Telegram, December 6, 1917.

IT PAYS TO ADVERTISE

Jeweler Collects All His Debts With One Piece in Paper(Glen Cove, L. I., Cor. New York Times).

Moescha Rosenberg's advertisement in the local paper had its desired effect. He threatened to print today a list of those who owed him money and would not pay. All week and right up to press time Rosenberg was kept busy receipting old bills, and now he says that there is not a resident of this village who owes him a cent. Rosenberg is a jeweler and is closing up his store. Several thousand dollars was due him, and he wanted it before he left town. So he put in the advertisement in which he said: "I shall publish the name and exact address and vocation of each of the aforementioned deadbeats, giving in my usual style a psychological treatise of their character and make-up. The paper goes to press at 10:30 a m., and all who are anxious to have their characters defined in print should not settle their accounts before that time."

Immediately creditors began to appear and pay their bills. Men who had bought engagement rings on credit and others who had purchased presents that they did not care to have published, all paid up promptly, and the jeweler was happy. So today Rosenberg, published an advertisement on "Soiled Linen," in which he said: "There are those who firmly believe that there is no wrong that could not be corrected. That it all depends on the laundry. Some linen must be badly soiled, but all can be cleansed. It depends on how hard one rubs. We are glad to state that not one dollar that was owing to us last week is unpaid today. We do not want to congratulate our friends who paid up, but, rather, ourselves, as good, hard-rubbing launderers."

On December 11, 1917, the Brooklyn Daily Times reported that Rosenberg was leaving the jewelry business to become a pig rancher near Tulsa. I suspect he was joking, perhaps to suggest that he'd be happier dealing with pigs than his deadbeat Long Island customers.

The ex-jeweler who had stores also in Southampton and in Manhattan has disposed of all his business and abandoned his former vocation to conduct a pig ranch which he purchased near the city of Tulsa.

Three months later he had a 10-year lease on a prime space in a new shopping district at the south edge of downtown -- 5th & Main. He first appears in the city directory in 1919, living in rooms at 1408 S. Perryman Ave. Perryman Ave., named for the Muscogee Creek family whose ranch covered much of modern-day Tulsa, ran from 13th Street to 15th Street, and was renamed Carthage Ave. circa 1920 to conform to the city's new alphabetical street name system.

Soon thereafter, on March 16, 1919, Rosenberg, 43, had married Julia Goodman (née Finston), 29. Officiants were Rabbis Morris Teller and M. Himelstein, and the congregation was specified only as "Jewish Faith." At the beginning of 1920, according to census records, the couple lived at 1326 Perryman Avenue, in a building with three other families. On February 26, 1920, they had a son, Arthur Leonard Rosenberg, about whom more later. A 1920 city directory shows the family at 1436 S. Norfolk Ave., in an area demolished in the 1970s for part of the southeast interchange of the Inner Dispersal Loop -- a part that was never built. A daughter, Edna, was born to the couple in 1922. The 1923 city directory shows Mrs Julia Rosenberg at 1432 S. Norfolk, but no Moescha. Moescha's Miami obituary indicates that this is when he moved to Florida. 1436 S. Norfolk Ave. (Lot 2, Block 13, Broadmoor Addition) was purchased by Julia Rosenberg on February 12, 1920, and sold by her to Jacob Rosenberg on April 9, 1923.

In the 1930 census, the whole family turns up in Manhasset, North Hempstead, Long Island. By 1931, Moescha is in the papers again, but now in North Miami, having been robbed by three bandits of $100,000 in jewelry ($37,450 wholesale). His name turned up from time to time in newspapers for Florida's Jewish community. On November 6, 1931, the Jacobean reported that Moescha Rosenberg had returned from Manhasset to his home and had announced the opening of a new jewelry store on Lincoln Road in Miami Beach. In 1935, for Sukkoth (Feast of Booths or Tabernacles), Moescha invited up to a dozen men a day to come to the booth he set up at his home at 1728 Lenox Ave., Miami Beach, to converse with Rabbi Dr. Jacob H. Kaplan "the problems of modern life, such as the invited guest may suggest."

The 1935 Tulsa City Directory places Mrs. Julia Rosenberg once again at 1432 S. Norfolk Ave., with Beulah Cooper occupying the rear of the property (identified elsewhere in the directory as a maid, presumably occupying servants' quarters over the garage), and Mrs. Rose Finston (widow of Julia's brother Mark Finston, who was an executive with Bell Oil & Gas Co.) across the street at 1443 S. Norfolk. Someone named E. Frank Pumphrey lived at 1432 in 1934. Property records show that Rose Finston sold Lot 1, Block 13, Broadmoor Addition to Julia Rosenberg in 1937, who sold it on to Alice Osborn Cain in 1941. The lot had been in the Finston family since 1919. The State of Oklahoma purchased it in 1971 from R. G. & Lena Goodman for the never-built Riverside Expressway connection to the Inner Dispersal Loop.

Court records show that Moescha and Julia were divorced in Miami in 1935. He died on November 16, 1939. From the next day's edition of the Miami Daily News:

MOESCHA ROSENBERGFuneral services were conducted at 10 a. m. today in the Miami Jewish funeral home by Rabbi Abraham Kellner for Moescha Rosenberg, 74, retired diamond merchant, 1728 Lenox Ave., Miami Beach, who died yesterday. He came to Miami 16 years ago from Tulsa, where he is survived by a son and daughter. Burial was in Woodlawn Park cemetery.

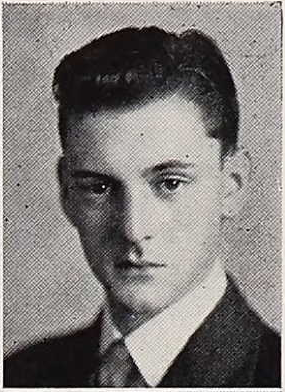

At some point, Julia and the children made their way back to Tulsa, where young Leonard attended Central High School, studied under legendary speech and drama teacher Isabelle Ronan (who also taught Paul Harvey), and graduated in 1937. (That's his senior yearbook photo on the right.) Julia, Leonard, and Edna were at 5 Riverside Drive, New York City, in the 1940 census, at the start of Leonard's long and successful career on Broadway and in radio, film, and television. You might remember him from The Odd Couple or Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? under his stage name, Tony Randall.

At some point, Julia and the children made their way back to Tulsa, where young Leonard attended Central High School, studied under legendary speech and drama teacher Isabelle Ronan (who also taught Paul Harvey), and graduated in 1937. (That's his senior yearbook photo on the right.) Julia, Leonard, and Edna were at 5 Riverside Drive, New York City, in the 1940 census, at the start of Leonard's long and successful career on Broadway and in radio, film, and television. You might remember him from The Odd Couple or Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? under his stage name, Tony Randall.

The Sinclair Building is in the news again. Having languished for several years under absentee ownership, the Ross Group is renovating it as apartments and retail space. Perhaps they will find a way to commemorate the first tenant of that coveted corner space (and his better-known son).

MORE: "Love, Lennie," a 2016 article in This Land Press by Charles Morrow: A brief biography of Leonard Rosenberg, aka Tony Randall, with a special focus on his Tulsa years and his later TV series, "Love, Sidney." The author's father had been a Central class of '37 classmate of Lennie, as he was known then: "When I asked Dad if they'd been friends, he frowned. 'No, he didn't talk to anybody. He was a snob.'"

TulsaTVMemories has several reminiscences of Tony Randall and his later visits to Tulsa. He spoke at the 1975 dedication of New Kendall Hall, having just learned earlier in the day that his childhood home had been demolished for an expressway. His driver that day, Edwin Fincher, recalls, "He was crushed, then cried, then cursed. He vowed to never come back again & made a horrible scene - live - during his speech on 'progress' in his old hometown, reading the original speech as it was written, but inserting 'remarks'."

0 TrackBacks

Listed below are links to blogs that reference this entry: Tulsa, May 1921: Moescha Rosenberg sues Sinclair.

TrackBack URL for this entry: https://www.batesline.com/cgi-bin/mt/mt-tb.cgi/8809