UTW Column Archive Category

If you went looking for BatesLine recently and found nothing, it's because the server was offline from late Tuesday, July 13, 2021, until sometime Wednesday evening, July 14, 2021. According to BatesLine's hosting provider, the downtime was "due to a MAC address conflict after a chassis swap. However, they were unable to boot the server up by different means. As a last resort, they have restored guests from backup to idle hypervisors." Sounds like a planned upgrade (which we weren't notified about) that encountered a problem that should have been anticipated.

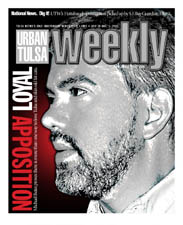

Just before everything went haywire, I added a couple of my old Urban Tulsa Weekly columns to the archives.

As faithful readers will no doubt recall, I wrote the weekly "Cityscope" column for UTW from September 2005 to May 2009. The newspaper ceased publication in November 2013 and the newspaper's web presence vanished shortly thereafter. Unfortunately, the website was set up in a way that was hard for the Internet Archive to navigate, and much of the site's content has been lost.

I kept copies of everything I submitted and retained my rights. (I stopped writing for UTW in May 2009 because I refused to sign the new freelancer's agreement which would have given UTW full "work for hire" rights.) Very slowly, over time, I've been posting those old columns and feature stories here, in the UTW Column Archive category.

Here are the two additions:

A recent essay by Addison Del Mastro calling for shared parking in suburbia prompted me to post my April 29, 2009, column proposing a parking pool for businesses and churches along Cherry Street and outlining a mechanism to make it worthwhile for all concerned.

In November 2008, I wrote a piece linking Thomas Kinkade, "painter of light," to urbanist Christopher Alexander, showing how Kinkade's paintings exemplify many of the patterns that comprise Alexander's Timeless Way of Building.

Although his work may be sold in suburban malls to be hung on suburban walls, the realities of suburban life do not intrude onto Kinkade's canvas.In Kinkade's cityscapes, the townhouses and commercial buildings come up to the sidewalks and have windows that allow passersby to see inside. In his neighborhood scenes, the houses have porches and big windows facing the street.

The buildings have eye-catching details above the windows and along the rooflines. The scale of the buildings and the details are proportionate to the pedestrians passing by. The light is gentle, coming through building windows, from small lights reflecting on the façade or signage, or from subdued streetlights....

Kinkade's paintings sell because they depict places where people want to be, places that are full of life.

But thanks to zoning laws with their setbacks and segregations by use and minimum numbers of parking spaces, thanks to modern commercial building practices and lending practices, thanks to indiscriminate demolition and the lack of conservation ordinances, places like these are harder and harder to come by.

And so instead of inspiring in their suburban owners the hope of living in such a place, these paintings embody a bittersweet nostalgia for the kind of streets that, they have been led to believe, can not exist in the modern world. Oh, maybe in a big city on the east coast, or over in Europe, but not in a sprawling Sun Belt metropolis like Tulsa....

Imagine that Tulsa could be so beautiful and full of life that people who had never been here would hang paintings of our streetscapes on their walls and dream of someday coming here.

More to come, eventually.

Not long after the demise of Urban Tulsa Weekly, its online archive went dark. Because of the structure of the urbantulsa.com website, many of its stories were never crawled by the Internet Archive. My attempt a couple of years ago to raise the $1200 needed to put the archive back online failed by a wide margin. (Gyrosite still has the archive and, last I checked, could still resurrect it, if anyone has the money and interest to do so.)

Not long after the demise of Urban Tulsa Weekly, its online archive went dark. Because of the structure of the urbantulsa.com website, many of its stories were never crawled by the Internet Archive. My attempt a couple of years ago to raise the $1200 needed to put the archive back online failed by a wide margin. (Gyrosite still has the archive and, last I checked, could still resurrect it, if anyone has the money and interest to do so.)

As a freelancer, I retained copyright to the columns and feature stories I submitted to UTW. In fact, it was my refusal to sign a new freelancers' agreement with the paper, in which anything a freelancer submitted would be work-for-hire -- owned by the paper, with no rights retained by the creator -- that led to the end of my column after 3 years and 9 months. As I wrote at the time, "What if UTW is sold to a chain of weeklies or goes out of business? (God forbid on both hypotheticals.) Those possibilities seem very remote today, but a lot can happen in 10 or 20 years, and if they happened, who would own the rights to my work under the agreement? Would I be able to get permission to use my own work? Who knows? At the very least, I would want to continue to retain enough rights for anything I write to be able to keep it accessible on the web." As it happened, it only took a little over four years for one of those hypotheticals to come to pass.

I made sure to keep the pre-edited versions of all my stories, as I submitted them. As I have occasion and time, I am posting my columns, as submitted, in this UTW Column Archive category here on BatesLine. As of September 10, 2017, I have about 20% of what I wrote posted. At some point, perhaps, I'll get the rest of them online, along with an index.

An edited version of this column was published in the May 28 - June 4, 2009, issue of Urban Tulsa Weekly. This was my final column for UTW, for reasons I explained in a blog entry at that time. The final paragraph was cut by the editor. The published version is available on the Internet Archive's Wayback Machine. Posted October 25, 2022.

Cityscope

By Michael D. Bates

Notebook

Tulsa Police Chief Ronald Palmer has proposed imposing a security fee of 75 cents to a dollar per ticket to cover the overtime costs for extra police officers patrolling downtown during major BOK Center events. It's the least that the BOK Center can do to offset its impact on the city budget.

It's argued that such a fee would upset the promoters who book shows at the arena, putting Tulsa at a competitive disadvantage. If someone is willing to buy that ticket for a dollar more than previously, that's a dollar that could have gone to the promoter instead of the city. The argument goes that the BOK Center is generating sales tax revenue, and we shouldn't balance the city budget on the backs of these promoters.

In reality, the voters chose to subsidize those promoters to the tune of $178 million, and it will take at least a century for the arena to generate the same amount of local tax dollars that we put into it.

Here's the math: The BOK Center has remitted over $1.2 million in city and county sales tax revenues in the eight months since it opened. It's impossible to know exactly how much of that revenue came from Tulsans reallocating their disposable income from other entertainment and dining options, although it's reasonable to think that the vast majority of the revenue is coming from local residents.

In the six months reported by the Oklahoma Tax Commission since the arena held its first paid event last September, sales tax receipts in Tulsa County increased by 4.7% over the year before. But statewide, sales tax receipts for the same period increased by 5.5% over the year before, suggesting that the BOK Center didn't provide an added boost to Tulsa over and above the improvement to the general state economy.

But for the sake of argument, let's assume that all of the sales tax paid by the BOK Center represents new money. At that rate it would only take about 100 years for local taxpayers to recoup in city and county tax revenues the $178 million (not including interest on the bonds) that we put into the facility.

Former Councilor Chris Medlock, in his May 19 medblogged.com podcast, took debt service into account and calculated 122 years before the arena will generate as much local sales tax as was spent to build it.

My calculation and Medlock's figures both optimistically assume that the BOK Center will continue to bring in big acts and draw the same big crowds as it has during what Bolton has called a "honeymoon period," although Bolton himself has warned Tulsans not to expect that to happen.

No one can know for sure whether the BOK Center has increased local tax receipts over what they would otherwise have been. What we can say for sure is that popular music venues like Cain's Ballroom, the Marquee, and the Mercury Lounge haven't been subsidized by taxpayers to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars. The owners of those venues paid to rent or buy and to renovate their facilities. Those costs are passed on in the price of each ticket.

BOK Center management and show promoters should be overflowing with gratitude to the taxpayers of Tulsa County for giving them, at no cost to them, a brand new, state-of-the-art venue where they can put on their shows and make big profits. They shouldn't try to dump even more of their operating cost onto city taxpayers.

# # #

Anytime I hear about a downtown church expanding, I cringe. For many years, that has meant that another historic commercial building will fall to make way for more parking.

It's wonderful that our downtown churches, with their historic and beautiful buildings, have survived and continue to thrive, drawing congregants from all over the metropolitan area, but their hunger for surface parking makes them a mixed blessing.

First Presbyterian Church's approach to expansion, however, deserves praise and warrants emulation.

Rather than tear down the old Masonic Temple across Boston Ave., Tulsa's oldest congregation renovated it for use as church classroom and event space and offices for non-profit organizations. Now called the Bernsen Community Life Center, it serves not only the church but the whole community. Barthelmes Conservatory, for example, has its office there and holds its public concerts in the center's various performance spaces.

In the same spirit, First Pres is about to eliminate some surface parking and put something beautiful in its place. A new worship center and reception hall, welcome center, and educational building will fill up the half-block west of Cincinnati Ave between 7th and 8th Streets. The new additions will be in the same Gothic Revival style as the 1925 sanctuary. The buildings will form a U around a courtyard, reminiscent of a cathedral cloister.

The church has also acquired the Power House gym at 8th and Detroit, which served many years as Chick Norton (later Jim Norton) Buick - one of the few downtown auto dealership buildings still standing. Power House is the new home for the church's youth ministries, and it is already under renovation.

The congregation has pledged over $14 million toward a goal of $18 million, to be matched dollar-for-dollar by Charlie Stephenson, a co-founder of Vintage Petroleum, and his wife Peggy.

There was something else on the drawings that I found especially encouraging: A new parking garage on the southeast corner of 7th and Main, directly to the west of the Bernsen Center, taking the place of an existing surface lot. It's not clear whether this is part of the current fundraising drive or something for the future.

A parking garage would set a great example for other downtown churches, by accommodating more cars in a smaller area. It would be even more exciting if the garage included street-fronting retail spaces, which would help rebuild a pedestrian-friendly connection between the downtown office core and TCC and the south downtown churches.

# # #

I'm told that, after the first week of the PLANiTULSA survey, ranking four scenarios for future growth, only about 600 had been collected or submitted online at planitulsa.org. Planners are hoping for 20 to 30 times that number by the June 18 deadline.

Please take time to submit a survey: The more Tulsans participate, the harder it will be for city officials to ignore the results.

As it's my 194th and final weekly column for Urban Tulsa Weekly, here are three parting observations about PLANiTULSA:

1. PLANiTULSA is finally delivering what Bill LaFortune promised with his July 2002 "vision summit." 1100 Tulsans gathered to express their dreams for the city's future, but instead of the process leading to a comprehensive strategy and plan for Tulsa's future development, the result was a grab-bag of disconnected projects scattered around the county.

With the PLANiTULSA process, Tulsans are finally putting together a vision of the sort defined by futurist Glenn Heimstra at the 2002 summit: "A compelling description of your preferred future."

2. The results of the PLANiTULSA citywide workshops, represented by Scenario B, and to a lesser extent by C and D, vindicate the "Gang of Four" - Councilors Jack Henderson, Jim Mautino, Chris Medlock, and Roscoe Turner, who served together from 2004 to 2006 - as genuine advocates for the City of Tulsa's growth.

The four took a lot of flak from the development industry, which pushed the unsuccessful 2005 attempt to recall Mautino and Medlock. They were tarred as opponents of growth, but the quartet's real offense was working to focus Tulsa's resources on encouraging new, high quality, compatible growth within Tulsa city limits rather than fueling suburban expansion at Tulsa's expense.

Those efforts began in 2003, when Medlock and then-Councilor Joe Williams proposed a future growth task force to address the stagnation of the city's sales tax base as new retail followed residents to the suburbs.

The task force was put on the back burner by Mayor Bill LaFortune, but in 2004, the coalition won funding for a study potential big-box retail sites in Tulsa. The Buxton study identified US 75 at 71st St a prime location to capture retail dollars from customers in upscale suburban subdivisions. Medlock won approval of a Tax Increment Finance district for the area, which made possible the development of the Tulsa Hills shopping district.

The four, along with Sam Roop (for a time), held up the reappointment of two members of the Tulsa Metropolitan Utility Authority, the city's water board, over concerns that the TMUA's long-term water deals with the suburbs benefited suburban growth to the City of Tulsa's detriment.

This same coalition began pushing for a new comprehensive plan in 2005 and included funding for the process we now call PLANiTULSA in the 2006 Third Penny package.

Assuming survey responses reflect the same preferences on display at last fall's workshops, it will confirm that Tulsans share the desire that motivated these often-vilified councilors: to see new development in the City of Tulsa that respects existing neighborhood character, brings more people into the city, stimulates new retail development, and generates more tax revenue to fund basic city services.

3. In my very first UTW column, back in September 2005, I wrote of the importance of walkable neighborhoods for Tulsans who don't have the option of driving a car.

"Most of Tulsa is designed for the private automobile, but there ought to be at least a part of our city where those who can't drive, those who'd rather not drive, and those who'd like to get by with just one car can still lead an independent existence. At least one section of our city ought to be truly urban."

PLANiTULSA scenarios B and D would get us closer to making that goal a reality.

As you fill out your PLANiTULSA survey, by all means think about which scenario comes closest to the kind of city that would best serve your needs. But take a moment to consider which of the four scenarios would best serve those who by reason of age, infirmity, or poverty are unable to drive.

And with that I'll say goodbye for now. I'm grateful for the opportunity to have been part of the UTW team for almost four years. Many thanks to the UTW readers who took time to read my words, who wrote in with praise and with criticism, and who voted my blog, batesline.com, Absolute Best of Tulsa two years in a row. Best wishes for continued success to the staff, management, and advertisers of Urban Tulsa Weekly.

An edited version of this column was published in the May 21-27, 2009, issue of Urban Tulsa Weekly. The published version is available on the Internet Archive's Wayback Machine. Here's my blog entry linking to the article. The date of the PLANiTULSA scenario rollout was May 12, 2009, not March 13. Posted October 25, 2022.

Cityscope

By Michael D. Bates

Which scenario is rosiest?

About 500 Tulsans were present at Cain's Ballroom on Tuesday, March 13 [May 12], to see the unveiling of four scenarios for Tulsa's future growth and development. A short presentation was followed by dozens of spirited conversations that spilled out on to Main Street and down the hill into Soundpony and Lola's and other Brady Arts District establishments.

The event launched a survey called "Which Way, Tulsa?" It's the latest step in the PLANiTULSA process of developing a new comprehensive plan for our city.

Four different directions have been offered for the public's consideration:

Scenario A, "Trends Continue": Continue along our current path, with most new development and population growth in the suburbs.

Scenario B, "Main Streets": New growth in and near downtown and along street and transit corridors. These corridors become like Main Streets, centers of activity for the surrounding neighborhoods.

Scenario C, "New Centers": New growth is concentrated in and around new hubs of activity with significant concentrations along N. Peoria; along 21st & 145th East Ave. in east Tulsa, and along US 75 south of I-44 in southwest Tulsa.

Scenario D, "Centered City": New growth is focused on downtown and surrounding areas and along transit corridors; the lion's share of transportation dollars goes to mass transit instead of roads.

Scenarios B, C, and D all represent a significant departure from the trend. Although the three differ in emphasis, you can find elements of each in the other two. All three involve medium- to high-density development in downtown. "Main Streets" has new centers (albeit less concentrated) along the BA at Memorial and Garnett, and around 71st and US 75. "New Centers" and "Centered City" have Main Street development along 11th St., Peoria, and elsewhere.

Between now and June 18th, Tulsans can express their preference by filling out the survey in the back of the glossy "Which Way, Tulsa?" brochure or rating the scenarios online at planitulsa.org.

In the days since the launch, I've heard a number of anxieties expressed about the survey and how the results will be used. Let me try to respond to the concerns.

First, it's important to understand that we're not voting on a final comprehensive plan. The maps may create the impression that, by voting for a particular scenario, you'd be voting to redevelop or up-zone a specific piece of land as depicted on the scenario map. That's not the case.

The general direction and preferences expressed in the survey results will be used to guide the planning team in creating a draft comprehensive plan.

But there are specifics - a lot of them - backing up each scenario. The Fregonese team placed specific types of development at specific locations, in line with each scenario's general approach, and fed those specifics into their computer models to calculate selected indicators, such as population growth, housing mix, job growth, commute time, land consumption, and emissions.

The indicators that were deemed to be of general interest were published in the Which Way, Tulsa booklet; more can be found on the planitulsa.org website.

The survey at the back of the booklet (and online) allows you to choose the preferred scenario according to each of seven different criteria and then to pick an overall favorite and second favorite scenario.

The planning team will tabulate the survey results and create a draft comprehensive plan. What that plan looks like will depend on whether one scenario is a strong favorite or multiple scenarios have strong support. If a favored scenario is weak for a specific criterion, the draft plan would be tweaked accordingly to address the shortcoming.

The draft plan, which will be detailed and specific, should be released sometime this fall. Public feedback will be used to refine the draft comprehensive plan before it goes to the Tulsa Metropolitan Area Planning Commission (TMAPC) and the City Council for adoption.

But there's much more to be done once the plan is adopted. City officials will have to decide if and when to fund new roads and transit. Scenarios B, C, and D all assume the use of new mixed-use development types that are either illegal or not economically feasible under Tulsa's zoning code and development standards. The city's ordinances will need to be amended if we want to depart significantly from our current development trend.

Even then, it will still be up to private developers and investors to turn development concepts in the plan into real buildings and neighborhoods.

Another frequently voiced worry goes like this: "There's a pink or purple blob right over my house! I like this scenario in general, but I don't want ugly infill development in my neighborhood."

The colors on the scenario maps, ranging from light pink to dark purple, show where new development would go and how dense it would be; the darker the color, the higher the density. The blobby shapes on the map aren't meant to be precise: "The four scenarios present generalized concepts of how the City can grow."

The guiding principles for the PLANiTULSA process, adopted in February by the citizens' advisory committee, affirm a commitment to protecting the history and character of our neighborhoods:

"Future development should protect historic buildings, area neighborhoods and natural resources while also enhancing urban areas and creating new mixed-use centers where people can find everything they need in vibrant communities. It's vitally important that the look and feel of new construction complement and enhance existing neighborhoods, rather than simply being added on."

Carrying out this principle, the PLANiTULSA team created a map showing areas of change and stability, accompanied by a statement which shows that the planners get the difference between good infill and bad (see sidebar). The areas of stability include "environmental areas such as rivers, creeks, floodplains, parks and open space; single family neighborhoods; and historic districts." In stable neighborhoods, compatibility would be the foremost criterion when building on a vacant lot or replacing a dilapidated structure.

Even if we treat areas of stability as off-limits for new development, there's plenty of room to accommodate more people and jobs within the Tulsa city limits. Scenarios B, C, and D would see Tulsa grow by 72,000, 101,000, and 102,000 new residents respectively, three to four times the 28,000 new residents we can expect if the current trends continue.

How we house all those extra people is where C differs significantly from B and D.

Under scenario C, two-thirds of additional housing over the next two decades would be single-family. That's consistent with current ratios.

Under scenario B, only a third of new housing would be single-family. Half would be multi-family and the remaining sixth would be townhouses.

Scenario D drops the single-family share down to 19 percent. Two-thirds would be multi-family, and 14 percent would be townhouses.

Despite the big differences in the mix of types for new housing, the total housing mix (old plus new) would remain majority single-family under each scenario.

For one of my friends, a resident of a suburban Tulsa subdivision, the lowest proportion of multi-family housing was reason enough to pick scenario C. But don't dismiss B and D, just because you don't like the way Tulsa has traditionally built apartments.

For many Tulsans, the phrase "multi-family housing" carries connotations of transience and impermanence, terms that could apply to the buildings and to the people who live in them. An apartment, the thinking goes, is where you live when you're just out of college or when you can't afford to own a home.

For suburbanites, multi-family calls to mind sprawling apartment complexes. Midtowners may think of the up-zoning of Riverview and Kendall-Whittier about 40 years ago from single- to multi-family, as one craftsman bungalow after another was torn down and replaced with a flat-roofed, four-unit apartment building on the same lot.

But multi-family can also mean luxury condo towers or the sort of sturdy, brick, three-story apartment buildings that coexist harmoniously with single-family homes in the Swan Lake historic district.

By lumping all types of multi-family housing together in a single percentage, the "Which Way, Tulsa?" material fails to paint a clear picture for the citizen weighing each scenario's pros and cons.

The detailed indicators (which you can find at planitulsa.org/agendas under the April 14, 2009, meeting) show that the bulk of multi-family housing for scenarios B and D would be in mixed-use developments combining residences with retail and office space. Only 15 percent of new housing units would be apartments in strictly residential developments.

It's my sense that many Tulsans would prefer not to have the hassle and expense of maintaining their own home and would opt for multi-family housing if a greater variety of living situations were available, particularly if it meant being able to live near jobs, shopping, entertainment, and transit.

I'm still mulling it over, but at the moment I'm leaning toward scenario B. The "Main Streets" concept seems to make the best use of existing infrastructure, while reconnecting Tulsa's urban fabric and improving walkability for more neighborhoods, helping to create the kind of city I'd like for myself and my children.

Whatever your preference for Tulsa's future growth, be sure to express it by filling out the "Which Way, Tulsa?" survey.

# # #

SIDEBAR

The four scenarios present generalized concepts of how the City can grow. As we move forward with the plan, we will refine desired growth patterns to target areas that Tulsans have told us will benefit from new investment and revitalization, such as undeveloped land, struggling commercial corridors, vacant lots or vacant and underutilized nonresidential sites. We will also respect areas of stability and historic significance, such as single-family neighborhoods.The term "infill" can have a negative connotation. It is often used to describe huge houses or apartment complexes out-of-scale with existing neighborhoods. PLANiTULSA intends to differentiate good infill from bad infill. Good infill should add appropriate development that a neighborhood has been missing. Good infill is the right use and scale and adds to the overall neighborhood.

Good infill often takes place at the edge of an existing neighborhood that could benefit from a new cafe or small grocery store. Reinvestment in a dilapidated home or building a townhome on an empty lot can help improve property values. Infill development can and should be considered a community benefit when done appropriately and sensitively.

The following maps show areas where change is quite possible and other areas that should remain stable in their current form. The areas of potential change could experience new investment in the form of infill, new development and construction. In areas of stability, the focus is on programs to protect and enhance existing neighborhoods.Mapped areas of stability include environmental areas such as rivers, creeks, floodplains, parks and open space; single family neighborhoods; and historic districts.

While the areas of potential change and areas of stability map is not a parcel by parcel map, it is intended to show overall how different areas of the city will be treated in the Comprehensive Plan. This differentiation in types of areas will be carried through into policies that treat areas of change (for example an abandoned industrial site) different than areas of stability (an existing single family neighborhood.)

An edited version of this column was published in the May 14 - 20, 2009, issue of Urban Tulsa Weekly. The published version is available on the Internet Archive's Wayback Machine. Posted October 25, 2022.

Cityscope

By Michael D. Bates

Downtown Tulsa Unlamented

The departing head of Downtown Tulsa Unlimited (DTU) reflected with satisfaction on his 20 years of service. He told the business reporter:

"Our downtown is destined to be one of the outstanding downtowns. No other downtown association got into the nitty gritty. All our programs have been successful....

"We're no longer trying to save downtown....

"We needed to get the cheap joints out. We formed the old urban renewal authority and it has been effective. We cleared out the old, obsolete areas...."

Those words came from L. A. "Bud" Blust, Jr., who served as DTU's head from shortly after its inception in 1956 until 1977.

As his fourth successor, Jim Norton, leaves DTU this month after his own two-decade stint, it's a fitting time to look back at the downtown organization's history and its future, if any. DTU's policy successes ultimately led to the very result the group was formed to prevent: The collapse of downtown retail.

DTU was founded by downtown retailers concerned about growing competition from new suburban shopping centers, although from the beginning its membership included other downtown businesses and organizations.

In 1951, Froug's opened a branch in the new Eastgate Center at Admiral and Memorial. Utica Square debuted in 1952 as a middle-class shopping center, complete with a bowling alley and T. G. & Y. (For you young whipper-snappers, T. G. & Y. was a chain of five-and-dime stores, sort of like a Walgreens minus the pharmacy and food, plus fabric and patterns.)

In 1956, Sears Roebuck decided to move from 5th and Boulder to 21st and Yale, near new edge-of-town subdivisions like Lortondale and Mayo Meadow.

DTU deserves much of the credit - or blame - for what happened to downtown over the next half-century. The 1959 "Plan for Central Tulsa," initiated by DTU and developed by planners from California, introduced the notion of a Main Street Pedestrian Mall, closed to traffic, and a superblock office/retail complex, called Tul-Center, to replace several blocks of old retail buildings around 1st and Main.

The same plan endorsed earlier proposals to clear a mixed residential and business area west of Denver Ave. for a multi-block civic center and to create a loop of expressways around downtown to make it easy for drivers to come in from the suburbs.

DTU lobbied very effectively to get the city to use federal highway and urban renewal dollars to accomplish these "progressive" plans, although it took until 1981 to complete all the projects. By the time Tulsa finished, other cities had already begun to rethink and remove inner city expressways, pedestrian malls, and superblock developments.

A Sept. 23, 1984, Oklahoman story celebrated the state of downtown Tulsa, which seemed to remain healthy despite the oil bust that had begun two years earlier.

The expressway system made it easy for people to live in the suburbs and commute to work and church in downtown. But creating the IDL wiped out apartments and homes and blighted nearby neighborhoods. More people coming from further away meant greater demand for parking.

As new skyscrapers went up and as downtown churches drew members from all over the metro area, one- to three-story buildings came down to make way for surface parking lots. These are the same sort of old buildings that have served as affordable venues for unique new businesses in Cherry Street, the Brady District, the Blue Dome District, Brookside, and 18th and Boston.

Retail followed the commuters and their families out to the edge of the city and ultimately into the suburbs. Office workers were in their offices, working, not out shopping.

One by one, downtown stores closed. An indoor mall, the Williams Center Forum, lingered for a bit longer, before being converted to office space in the early 1990s.

In 1977, Bud Blust was happy to be rid of the "cheap joints" (a description that evidently included ornate downtown movie palaces like the Ritz, Orpheum, and Majestic). But those old buildings, however seedy their occupants, had the kind of character that new construction in the suburbs could never duplicate.

In trying to imitate suburbia, DTU failed to win back customers who still found it easier to shop Southroads or Woodland Hills than to navigate the confusion of a street grid that had been hacked to pieces by downtown "improvements." At the same time DTU discarded the uniqueness that made going downtown worth the extra trouble.

You might think that a downtown merchants' association would close down once most of the merchants were gone, but DTU stayed alive, thanks to the business improvement district (BID) that was put in place in 1981. The City contracted with DTU's subsidiary, Tul-Center, Inc., to maintain the Main Mall and downtown plazas and sidewalks, funded by an assessment on properties within the BID. (DTU's executive committee serves as Tul-Center's board of directors.) Tul-Center, in turn, contracted with other providers and with DTU to do the actual work. (That at least was the arrangement early on, according to news accounts of the time.)

As retail faded away, DTU seems to have into an office-building owners association. Critics say that DTU represents the interests of only a small number of downtown property owners, but city officials continued to treat it as if it were the sole spokesman for downtown.

The same critics note that most of the entrepreneurial initiative has come not in the center, where DTU's attention has been focused, but on the edge of downtown, in places that DTU either overlooked or hoped at some point to wipe out.

In 1981, planners hired by DTU recommended clearing the area we now call the Brady Arts District to make way for an "urban campus." One of the planners was quoted in an April 7, 1981, news story as saying, "There's not really much character left in the Old Townsite, so we see no reason to restore it, as some cities have done to their original site." Thank goodness they never found the money to make it happen.

If Tulsa voters had followed DTU's advice and approved the "Tulsa Project" sales tax in 1997, Hodge's Bend--the area around 3rd and Kenosha, home to Tiny Lounge, Divine Barbering, and Micha Alexander's Virginia Lofts, featured on the cover of UTW a few weeks ago--would have been bulldozed for a soccer stadium.

It angers and amuses me to hear anyone claim that downtown's problem is government neglect and lack of public investment. Quite the opposite: Downtown Tulsa has been nearly loved to death.

A report on Tulsa's downtown issued earlier this year by an advisory panel from the International Downtown Association (IDA) enumerates the many ways in which the planning fads of earlier years hurt downtown's vitality.

When the panel of four visited downtown last November--just before the Tulsa Run--it concluded that "Downtown Tulsa is stuck in a time warp":

"A first-time visitor to downtown Tulsa may be somewhat mystified. Streets and sidewalks are clean and well-lighted. A collection of handsome, even extraordinary art deco buildings adorn the office core. A strikingly designed arena stands dramatically on the edge of downtown, complemented by perhaps the most attractive new City Hall in America. Here and there, a café or coffee house lights the street. And yet... where are the people? ...

"There are few street level establishments of a retail nature. Windows facing the street are far too often dark. The hustle and bustle that today characterizes many downtowns across North America is simply absent."

We wish DTU President Jim Norton well as he moves on to his new position in North Carolina. I served with him on a couple of task forces and always found him to be courteous and congenial, despite our differences. To his credit, he has been an effective advocate for public funding for downtown infrastructure and incentives for residential development.

One could fault him for his opposition to modest historic preservation and urban design measures--the sort that most other cities our size, including Oklahoma City, have had for many years--but it's important to remember that he was merely representing the interests of those who control DTU, those who hired him and who had the power to fire him, and not necessarily the best interests of downtown as a historic urban center.

DTU's days may be numbered. Rather than continue the 28-year exclusive arrangement with DTU's Tul-Center subsidiary, the City is seeking competitive bids to take over public property maintenance services for the new Tulsa Stadium Improvement District, which will also fund the Tulsa Drillers' new stadium. Bids are due to the City Clerk's office by 5 p.m. on May 20. (You can find the invitation to bid and the detailed requirements for the contract at cityoftulsapurchasing.org. The bid number is TAC 843.)

Tul-Center is competing for the contract. If they lose, DTU could theoretically continue to exist, but that may not be feasible. According to the IDA report, "DTU relies on the BID assessment for its very existence. BID revenues constitute about 9 out of every 11 dollars passing through DTU each year."

In my opinion, DTU's time has long since passed, and, contrary to the recommendations of the IDA, there's no justification for giving it pride of place in a new "Downtown Coordinating Council."

A single organization representing everything within the Inner Dispersal Loop is at once too broad and too narrow. Within the IDL there are condo owners, small retailers, nightclubs, old apartment buildings, art galleries, and office buildings. No one group can adequately represent such a diverse collection of interests.

But if there is to be an umbrella organization to represent common concerns of those diverse groups, its coverage should extend beyond the IDL to include the surrounding neighborhoods. The revival of central Tulsa requires regenerating the connections that were severed when the expressways were built.

Let the winning bidder for the public property maintenance contract stick to providing exactly those services and nothing more. The City should not accord the winning bidder status as de facto spokesman for downtown. Instead, the City planning department should take the lead role, even-handedly weighing input from central Tulsa stakeholders-neighborhoods, associations, institutions--as they implement a new comprehensive plan.

DTU failed to serve its original purpose, and no longer serves any public purpose at all. Let it go on independently if it will, but fifty-three years of taxpayer-subsidized failure is enough.

An edited version of this column was published in the May 7 - 13, 2009, issue of Urban Tulsa Weekly. Here is the blog entry I wrote at the time, linking to the column, and a blog entry reporting on the rollout. The published version is not available online. Posted October 25, 2022.

Cityscope

By Michael D. Bates

PLANiTULSA scenario launch

In just under a week, PLANiTULSA will launch a public survey, asking Tulsans to rate four scenarios for our city's future growth and development. The survey is expected to draw the most participation of any step in the year-and-a-half-long process of developing Tulsa's first new comprehensive plan in a generation.

It's also the final significant opportunity for public input, so it's important for you to understand what the scenarios are, whence they emerged, and what will be done with the feedback you provide.

So pay attention! This is important. This material will be on the test.

The kickoff event for the PLANiTULSA survey will be at Cain's Ballroom on Tuesday, May 12, 2009, from 6 to 7 p.m. Described as "part pep rally, part social event," the party will be catered by Eloté Café (renowned for fresh Mexican food), with music by Little Chairs, a local roots rock band in the "Tulsa Sound" tradition.

Beyond the food and music, the goal of the kickoff is two-fold. In addition to giving citizens a chance to see scenario details and ask questions of the planning team, the aim is to generate enough buzz to get thousands of Tulsans to respond to the survey.

Planners are hoping for about 15,000 responses. That would be a very strong level of involvement compared to similar surveys that Fregonese Associates, lead planners for the PLANiTULSA process, have done for comprehensive plans in cities and regions around the country. There's hope that the enthusiasm that led to an overflow for last fall's citywide workshops will carry over to these surveys.

The six-county Grand Traverse region of northern Michigan went through the same process last October and November. 11,603 surveys were submitted, representing just under 6% of the region's population. (Visit thegrandvision.org to see their results.) A proportional response for Tulsa would be around 22,000 surveys.

The Fregonese team has put together four growth scenarios based on the input received during the citywide workshops last fall, each representing a different approach to new growth. One scenario represents continuing on with our current growth pattern; the other three represent frequently recurring patterns in the maps developed by workshop participants.

The Tulsa metropolitan area is projected to grow by 164,000 people and to add 53,000 jobs over the next two decades. The scenarios provide different answers to the questions that are at the heart of a comprehensive plan: How much of that growth do we want the City of Tulsa to capture? What do we want that growth to look like? Where in the city would we like it to go?

There's a related question Tulsans need to answer: How much of the roughly $2 billion that will be spent on new transportation infrastructure over the next 20 years should go to street and highway widening and how much toward various forms of mass transit?

How we answer those questions and the development policies we adopt as a result will influence the kind of city our children and grandchildren will experience.

Today's Tulsans are living with the impact of planning decisions made over 50 years ago, when our expressway network was mapped out and a development pattern for new neighborhoods was established. That pattern of single-use development, segregating where we live from where we work, shop, worship, study, and play, was enshrined in our vintage 1970 zoning code.

The Fregonese team has run each scenario through their modeling software to estimate the scenario's impact on population, jobs, commuting time, and demand for new infrastructure, among other key measurements.

I'll be able to provide a more definitive analysis once the final versions of the scenarios and the survey have been released. For now, here's a summary of the four scenarios, based on drafts that have been shown to the PLANiTULSA citizens' team, of which I'm a member.

As you read these descriptions, keep in mind that the planners have already taken out of play those areas which would be unlikely or controversial to redevelop. These "masked out" areas include single-family neighborhoods, historic preservation districts, parks, and floodplains.

Remember too that these descriptions are necessarily oversimplified. Maps showing new development, shaded to represent density, will be in the survey literature. I'm hoping that the website will provide more detailed information, showing the locations of different types of development and transportation as separate map layers.

Scenario A represents the current trend, which could also be called "business as usual," with the bulk of new development occurring in the suburbs, dominated by single-family housing. Under this scenario, only 17% of metro area population growth would take place within the Tulsa city limits. (The other three scenarios have Tulsa capturing 44% to 62% of metro area population growth.)

Scenario B is modeled after the aggregate of the more than 100 maps created by participants in last fall's citywide workshops. Workshop participants showed a strong preference for high-density, mixed-use development that brings together homes, jobs, shopping, and entertainment, as evidenced by the "chips" (representing various types of development) they selected and placed on their maps.

Scenario B, subtitled "Main Street Redevelopment," reflects this preference, putting the highest density development downtown and in nearby neighborhoods that want redevelopment, such as the Pearl District and Crutchfield.

While 62% of Tulsa's households are in single-family homes, only 33% of new development under Scenario B would be for single-family; the remainder would be multi-family and townhouses. (The resulting housing mix would still be 57% single-family, a shift, but not a massive one.)

Arterials that already have something of a Main Street character would see that character reinforced and extended, with mixed-use pedestrian friendly development replacing auto-oriented commercial development. For example, you might see a modern version of Brookside-type development further south along Peoria toward 71st, and along North Peoria as well.

Other opportunities for increasing density exist in other parts of the city, where underused retail centers and their vast, underused parking lots could be replaced with a mixture of apartments, townhomes, shopping, and offices.

Scenario B imagines turning industrial areas along highways and railroad lines into transit-oriented mixed-use development - for example, along the old MK&T tracks near 11th & Lewis, 41st and Memorial, and 51st and US 169.

Scenario C and D represent development approaches are variations that were each embraced by a substantial minority of workshop participants.

Scenario C, "New Centers," is similar to B in that it puts growth downtown and along key arteries. But it puts more emphasis on single-family housing, and it would create new centers of development in places like 21st St. & 145th East Ave., North Peoria, and near 71st St. & U. S. 75. These new centers would have housing, jobs, shopping, and services all in close proximity and would be linked by transit to one another and downtown.

Scenario D, "Central City," is the sustainable development option, with most of the growth downtown and near downtown. This option is the most effective at putting residents near parks and open space. It also consumes the least amount of vacant land.

Scenario D is the most transit-focused option, putting 73% of future transportation capital dollars to transit. Scenarios B and C are split 59% for road improvements and 41% for transit improvements. (The trend is 99% for roads, 1% for transit.)

I was surprised to see that, according to the Fregonese models, Scenario D's significantly higher transit investment only boosted the percentage of regular transit riders, pedestrians, and cyclists by two percentage points, from 15% for B and C to 17% for D.

(All three were significant improvements over the 5% transit/pedestrian share for Scenario A, the current trend.)

So now that the planners have put together these four potential growth scenarios, they're asking Tulsans for feedback. There will be a booklet showing each of the scenarios and how they compare on key indicators.

A survey on the back page will ask you to rank the scenarios on how well each fits your needs and desires for housing, transportation, and job options, and how they match the kind of city you want to live in. You can mail, fax, or drop off the survey.

You'll be able to answer the same questions online (via planitulsa.org).

The planners will use the survey results to put together a detailed comprehensive plan, which will be presented to the Tulsa Metropolitan Area Planning Commission (TMAPC) for consideration. The final draft may be a blend of scenarios, reflecting the likes and dislikes expressed in the survey.

Adopting the plan is a legislative act, so the final decision is with the City Council. As with any ordinance, the mayor could choose to sign or veto, and the Council could override a veto with a two-thirds vote.

The exact timing of the final steps is still up in the air. It would be ideal to have the draft plan presented to the TMAPC sometime in late summer, so that whether to adopt or not would be the central issue of this fall's city elections.

A big turnout at Cain's next Tuesday, May 12, would be a great way to launch this important public input process. I hope to see you there, but whether or not you can make it, please take time over the next few weeks to fill out a PLANiTULSA survey and let planners know how you want Tulsa to grow.

An edited version of this column was published in the April 29, 2009, edition of Urban Tulsa Weekly. The published version is no longer available online. Posted July 15, 2021. See the end of this entry for a postscript.

Cityscope

By Michael D. Bates

Parking wars

Will success spoil Tulsa's midtown entertainment districts?

In the '80s and '90s, entrepreneurs discovered the old retail buildings along 15th between Peoria and Utica. They converted the old storefronts into specialty boutiques, cafes, and nightspots. Since then, Cherry Street has become increasingly popular, a place that Tulsans like to show off to out-of-town guests.

That success has brought its share of challenges. One of those challenges: Where do you park if you want to visit more than one establishment?

I've seen the problem firsthand. About once a month, when my wife is at a moms' night out and my oldest son is at his violin lesson downtown, I take my two youngest children over to Cherry Street. They like Subway sandwiches for dinner, and while their palates aren't yet sophisticated enough to appreciate a "Hippie Sandwich" or a Greek salad at Coffee House on Cherry Street (known as CHoCS for short), they love the baked goods there, like the cream-cheese brownies and chocolate chip cookies.

CHoCS is right across the street from Subway, so you'd think it would simple to hit both in one trip. You'd be wrong.

I can't leave the car in the Subway parking lot after we finish our sandwiches and head across the street to CHoCS for dessert, because they have signs saying parking is for customers only, with a 15 minute limit and a $75 towing charge for violators. It's their property, and while I'd be upset if Subway had my car towed right after I bought a meal there, they'd be within their rights.

Neither do I want to take up one of the limited spaces at CHoCS while I'm at Subway. While CHoCS doesn't have any signs posted threatening a tow, their neighbors do. It's a popular place, and when the lot is full, some CHoCS customers have inadvertently parked in a space belonging to a neighboring business, only to find a warning note taped to the car, singling out CHoCS as the source of all the world's troubles. So as not to make a tight parking situation even tighter, I wouldn't think of parking in CHoCS's lot while visiting another Cherry Street merchant.

And I absolutely refuse to do something as stupid and wasteful as parking in one store's lot, getting back in the car, driving 100 feet, and parking in another store's lot. So instead of using either lot, I park in a public spot on a nearby side street, and my children and I walk to both destinations.

CHoCS' relatively easygoing attitude about parking is a rarity on Cherry Street, where signs threatening tow trucks and wheel boots are the rule. The every-merchant-for-himself arrangement discourages patrons from leaving their car parked in one place, strolling the street, window-shopping, and visiting several different retailers on the same trip.

Instead, a customer is more likely to park at the establishment he came to patronize, do his business, then get back in his car. Once he's back in his car, it's as easy (maybe easier) to head to someplace in Brookside or Utica Square as to go to another Cherry Street merchant.

The zeal to protect one's own parking is understandable, given the city zoning code requirement for each merchant to provide, individually, sufficient off-street parking for the worst-case scenario. By worst-case, I'm talking about the Best Buy lot on Christmas Eve.

To meet Tulsa's parking requirements, some merchants have had to purchase and clear entire house lots; they then need approval from the Board of Adjustment to use a detached parking lot. One restaurant has gone so far as to install automatic gates to protect its investment; you need the validation code from your dinner receipt to get out.

Under our current zoning code, approved in 1970, parking requirements are based on business type. Converting a storefront from a clothing store to a café triples the parking requirement. The requirements assume that everyone will be arriving by car and will be visiting only that one establishment before leaving by car.

But Cherry Street was developed before World War II, long before our current zoning code was put in place, to serve as a shopping area for residents within walking distance. Merchants weren't required to provide off-street parking, and for the most part they didn't. Customers could and did walk to do their shopping. Many stores would deliver.

When shopping districts like Cherry Street changed from serving nearby residents to serving customers from all over the city, parking became an issue. Years ago, cars would be lined up on Brookside's residential streets for blocks either side of Peoria. Residents had to deal with late-night traffic, cranked car stereos, and sometimes worse - drunken yelling, fights, and the public exercise of excretory functions.

The houses nearest Peoria were cleared and replaced with parking lots in order to meet the zoning requirements for restaurants and nightclubs. The new lots helped to keep the cars and the corresponding problems out of the residential areas. On a recent Saturday night research visit, I found there were almost no cars parked on the side streets, which were pretty quiet once I was a half-block or so away from Peoria.

Adding more parking lots as Brookside did would be harder to do for Cherry Street. Land north of 15th is at a premium; most of the land south of 15th is within a historic preservation district.

Even if the land were available, converting tree-lined lots to asphalt parking reduces available housing (and housing nearest the commercial area is often the most affordable), reduces shade, and creates an ugly, pedestrian-friendly moat of asphalt cutting the valuable link between the commercial and residential areas.

You might think that in an area like Cherry Street, with a variety of merchants whose actual parking demand ebbs and flows over the course of a day, that the merchants could pool their parking and reduce the total number of spaces required to make all the customers happy.

The zoning code doesn't make that possible, unless you have at least 100,000 sq. ft. in a single Planned Unit Development, and even then you only get to cut the parking requirement by 10% if the Board of Adjustment gives its permission.

Perhaps because of the extra parking lots, it appears that Brookside merchants are much more easy-going about parking than their Cherry Street counterparts. Most of the lots I mentioned above are available for anyone to use at any time - no signs to indicate who owns the lot or any restrictions on who can park there, no threats that Mater will come to haul your Lightning McQueen off to the impound lot.

For example, one church in the bustling heart of Brookside has a large parking lot, but restaurant and bar customers were parking there, and I didn't notice any signs forbidding it.

Brookside's open-handed approach to parking means that you can have dinner at a restaurant on one block, have drinks on another block, go dancing on yet another block, and cap the night off with coffee on yet a fourth block, all the while leaving your car parked in one spot.

I'm not sure how Brookside has managed this level of cooperation, but the district seems to accommodate the crowds without loading down neighborhood streets and without causing heartburn between merchants.

If Cherry Street merchants would pull together, they could work out a solution that would meet the needs of merchants, customers, and neighbors alike.

The solution I have in mind would respect the property rights of existing parking lot owners and would avoid eroding the neighborhood with more parking lots. My solution would require a minimal amount of government involvement and a willingness on the part of the merchants each to pony up a small amount of money - less than it would cost them individually to acquire more land for parking.

The solution is to create a business improvement district. Collecting the funds to provide shared facilities for a group of adjacent properties is exactly the sort of situation that an improvement district is meant to address.

The improvement district would cover property owners along Cherry Street, each of whom would pay an assessment proportionate to the degree of benefit from the district's improvements. The formula could be based on frontage, square footage, the number of parking spaces required by the zoning code, or some combination of those factors.

Assessment funds would be used to pay the owners of existing parking lots to open their parking spaces for the general use of customers of any merchant on Cherry Street. Lease payments could be based on the number of spaces and how many hours the spaces are available for general parking.

One lot owner might choose to make more money by allowing wide-open parking at any time. Another owner might choose to forgo some lease revenue, reserving her spaces during her peak business hours. Some lot owners would choose not to participate at all and would miss out on using their empty parking lot to generate some extra money. The more spaces you make available, the more hours you allow open parking in your lot, the more lease money you'd receive from the improvement district.

As a purely hypothetical example, a school might allow open parking except when the space is needed during the school day or for special events. The school could use parking revenues to fund special school projects.

Assessment revenue could also be used to pay for a few security guards to walk a beat on busy evenings, deterring vandalism and other kinds of misbehavior in the parking lots.

As a further incentive, the City Council could cut the required number of parking spaces for properties in improvement districts that provide shared parking.

Of course, the simplest and least bureaucratic solution for all concerned would be for the city to reduce off-street parking requirements to a reasonable level and for property owners to be more easy-going and open-handed about who parks where.

Failing that, a business improvement district may be the best way to defuse tensions among Cherry Street merchants and to allow customers to get full enjoyment out of one of Tulsa's finest shopping and dining districts.

POSTSCRIPT 2021/07/13: The problem persists. New construction on Cherry Street has taken more homes to the north to meet the parking requirements; meanwhile Brookside parking lot owners have become stricter about not allowing after-hours use of their lots. (The office building north of Shades of Brown Coffee recently deployed orange cones blocking the south entrance to the parking lot, and some years ago the office park to the west installed an automatic gate to prevent after-hours parking.)

Recently, Addison Del Mastro, a prolific writer on urban and suburban planning, raised a related issue affecting suburban commercial development:

As I've been driving around and exploring places, one of the interesting things I've run into is trouble parking.... the issue is that there's too much parking, but it's all private and specific to disconnected strip malls or office complexes (or churches!) ...it makes it pretty much impossible to walk in a suburban setting if you arrived by car (as most customers and visitors will.)On a more mundane and less conceptual level, the private, specific nature of suburban parking, with no public lots and little centrally located on-street parking, also means that there's no incentive or possibility to treat the commercial strip like a street, even if you want to. It's not unusual to hit two or three different shopping centers or stores on a shopping trip, some of which may be near each other. But you're technically risking getting your car towed if you walk off the property where you parked it.

Del Mastro asks, "What if these parking lots were treated as public and open?" You can read more of his work on his Substack newsletter, The Deleted Scenes, in the archive of his New Urbs columns for The American Conservative, and in City Journal, where his first piece has recently appeared, advocating for small towns as a model for denser but humane growth.

An edited version of this column appeared in the April 1, 2009, issue of Urban Tulsa Weekly. The published version is no longer available online. Posted online June 15, 2016.

Election Day 2009 is a mere seven months away, and a credible opponent to Mayor Kathy Taylor's bid for re-election has yet to emerge.

It is usual to set out one's reasons for seeking office in some form. In the U. S. we call such a document a platform; in the U.K. it's known as an election manifesto.

In that spirit, here then, on the 1st day of April, 2009, is my mayoral manifesto.

Transparency and accountability

We begin by acknowledging the financial constraints our city is under. The ideas listed below represent my priorities for spending the funds that we have. We will not propose or promote any measure that would increase the tax burden on the citizens of Tulsa, particularly in this time of financial uncertainty.

We will make the best use of the money that has already been entrusted to city government to provide basic services - police and fire protection, streets, water, sewer, trash, and stormwater. We will find the funds to conduct a thorough performance and financial audit of city government. We will insist on implementation of the recommendations and replace any department head that drags his feet.

We must increase the size and budget of our underfunded City Auditor's department. A properly-funded fiscal watchdog should be able to find more than enough savings to offset the additional cost.

To encourage transparency and accountability, a Bates administration will make as much city government information available on the internet as the law allows. A TGOV website will offer access to both live and archived video of public meetings.

A geographical information system (GIS) will make it easy for city workers and citizens alike to find information on zoning, crime, and construction in an area of interest. Accessible information will make it easier for citizens and media (both old and new) to keep an eye on city government and to uncover waste, fraud, and abuse.

Partnerships for progress

I pledge to build a collaborative relationship with the City Council, to respect their standing as the elected representatives of the citizens of Tulsa, and to treat them as partners, not adversaries.

If a councilor wants my ear, he won't have to go through three layers of underlings to get to me. If I'm attending a meeting or planning a project in a councilor's district, the councilor will hear about it ahead of time from me. Instead of sending out a flak-catcher, you'll see me at council committee meetings and delivering the weekly mayor's report. I won't agree to expensive legal settlements without the knowledge and consent of the Council.

Surveys have revealed a disconnect between City Hall and the citizens, particularly citizens in our less affluent neighborhoods in north, west, and east Tulsa. We need a sound civic infrastructure to keep citizens informed and to help citizens make their voices heard by city leaders.

One possibility is the district council plan used in St. Paul, Minn. My administration will survey best practices across the country and will work with the Council and neighborhood leaders to identify the model best suited to Tulsa's circumstances.

Membership of the city's authorities, boards, and commissions has been dominated by Tulsa's most affluent neighborhoods in midtown and south Tulsa. I will broaden the pool of mayoral appointees, starting by reaching out to the thousands of PLANiTULSA workshop participants.

I will collaborate with my suburban counterparts whenever appropriate, but I will never lose sight of the fact that I was hired to serve the citizens of Tulsa.

Planning and zoning

The PLANiTULSA process has been a great success to date, with thousands of Tulsans participating in citywide and small-area planning workshops. We should see the adoption of a new comprehensive plan prior to the city general election.

But the plan's adoption is only the beginning. Full implementation will almost certainly require modifications to Tulsa's zoning code. It will also require the political will to stick to the plan as individual zoning and planning decisions are made.

Tulsa's land-use planning system should be characterized by transparency, inclusiveness, consistency, clarity, and adaptability. Our land-use laws should allow as much freedom as possible while protecting against genuine threats to safety, quality of life, and property values.

We must get away from a one-size-fits-all zoning code. Development suitable for 71st and Memorial may not be right for 15th and Utica. Tulsa should establish special districts - some cities call them conservation districts - where rules can be customized to the neighborhood's circumstances. Form-based rules should be available for neighborhoods that want them.

Tulsa should do what every other city in the metro area has already done and establish our own city planning commission, one with a balanced membership that is geographically representative and not dominated by the development industry. All Tulsans have a stake in how our city grows, not just those who stand to make a buck on new construction.

We'll bring land-planning services in house as well, ending our contract with INCOG. (We will continue to collaborate with INCOG on regional transportation planning.)

Economic development

The city's approach to economic development would change in a Bates administration. Some of Tulsa's biggest employers and biggest draws for new dollars started small and grew.

Instead of spending all our economic development funds luring large companies to relocate to Tulsa, we should emphasize removing any barriers to small business formation and expansion.

One of those barriers is the cost of a place to do business. We'll revisit rules that hinder operating a business out of your own home. While many neighborhoods will prefer to remain purely residential, others would welcome the live-work option, with a broader range of permitted home occupations. Here again, Tulsa can customize rules to fit the diversity of our neighborhoods.

We cannot afford to leave behind those Tulsans who are at the bottom of the economic ladder. We will partner with non-profits to help Tulsans develop basic financial life skills - the habits that enable someone to find and keep a job, spend his earnings wisely, and build assets over time.

Tulsa should become known as a city of educational choice from pre-K to college for families of all income levels, not just the well-to-do. I will work with the Oklahoma legislature to expand access to charter and private schools for Tulsans. My administration will seek a cooperative relationship with private schools, homeschooling families and support organizations, and all seven public school districts that overlap our city boundaries.

Under my administration, the city will hold a full and open competition to choose a contractor to promote our convention and tourism industry. The Tulsa Metro Chamber will be welcome to compete, but no longer will it enjoy sole-source status. Tulsa is home to many innovative marketing firms that could do a better job of communicating Tulsa's unique appeal.

The city center

There's been a great deal of focus and hundreds of millions of dollars in public investment in downtown over the last decade. The aim of that investment was to bring downtown back to life, not to turn more buildings into surface parking lots. I will push for adoption of the Tulsa Preservation Commission's "CORE Proposals," including an inventory of downtown buildings, a demolition review process, and standards for new development that reinforce downtown's walkable, urban character.

But Tulsa's urban core doesn't stop at the Inner Dispersal Loop. Downtown's long-term prosperity and revitalization depends on the vitality of the nearby neighborhoods.

Tulsa offers many choices for those who prefer a suburban lifestyle, but we also need to provide a viable urban living option for individuals, couples, and families who want to live close to work, shopping, school, church, healthcare, and entertainment.

There should be at least one part of our city where you can go everywhere you need to go without needing a car. Central Tulsa was built with the pedestrian in mind. New development should reinforce its walkable character.

The city's role would be to protect stable and historic single-family neighborhoods, improve regulations and raise awareness of tax incentives to encourage adaptive reuse of historic buildings, and encourage higher-density, urban infill development in neighborhoods that desire it.

Getting around town

In the future, it may make financial sense to build a light rail system. Right now, we can make better use of the transit system we already have by focusing on frequent, dependable bus service from early morning to late night within this pedestrian-friendly central zone.

Where it's impractical to provide frequent bus service, entrepreneurs should be allowed to fill in the gaps. It ought to be possible in Tulsa for someone with time and a vehicle to make money helping their neighbors get around town. We'll study what other cities have done to encourage privately-owned, publicly-accessible transportation like jitneys, taxis, and shuttles.

Preparing for the future

A Bates administration will not only focus on the near term but will plan for the future as well. Disaster preparedness is a part of that job. One area that deserves attention is the security of Tulsa's food supply. A food crisis could be triggered by financial collapse, soaring energy prices, or a terrorist attack on America's food supply system.

City Hall should study ways to help connect local farmers and growers with local consumers so that our region can attain a degree of self-sufficiency and insulation from an external crisis. We'll make sure that city regulations don't get in the way of community gardens and farmers' markets.

If elected, I will govern with the expectation that I will only serve a single term. I will reckon myself a political dead man, having stepped on so many toes that millions will be raised to prevent my re-election as mayor or my election to any other office.

Finally, my fellow Tulsans, as you find yourself elated or, more likely, outraged at the thought of a Michael Bates mayoral run, remember the old Roman motto: Caveat lector kalendas Apriles.

An edited version of this column was published in the November 26, 2008, edition of Urban Tulsa Weekly. The published version is available online at the Internet Archive's Wayback Machine. Here's my blog entry linking to the article. Posted July 13, 2021.

Urban lessons from the Painter of Light

My topic for today is the artistic vision of Thomas Kinkade and its implications for urban design.

I'll pause while you roll your eyes.

Earlier this month, Vanity Fair magazine published an item on its website titled, "Thomas Kinkade's 16 Guidelines for Making Stuff Suck."

The piece was occasioned by the discovery of a memo the Painter of Lightâ„¢ issued to the makers of his film, Thomas Kinkade's Christmas Cottage, advising them how to recreate on celluloid the trademark "look" that has sold millions of prints of his paintings and made him a very wealthy man.

The guidelines include darkening around the corners and edges of the frame to create a cozy look, keying colors to the desired mood ("cooler tones to suggest somber moods, and warmer, more vibrant tones to suggest festive atmosphere").

Kinkade told the filmmakers to use a standing adult's eyepoint, rather than "off-kilter vantage points," to include in each scene "dramatic sources of soft light" ("dappled light patches, glowing windows, lightposts"), and to prefer a "gauzy" look to hard-edged realism.

Schlock and kitsch, you shout, and I won't stop to debate the artistic merits (or lack thereof) of Kinkade's cinematic vision.

But I was struck by a couple of points toward the end of his list of guidelines:

"Favor shots that feature older buildings, ramshackle, careworn structures and vehicles, and a general sense of homespun simplicity and reliance on beautiful settings."

"Older buildings are favorable. Avoid anything that looks contemporary -- shopping centers, contemporary storefronts, etc."

"Hidden spaces. My paintings always feature trails that dissolve into mysterious areas, patches of light that lead the eye around corners, pathways, open gates, etc. The more we can feature these devices to lead the eye into mysterious spaces, the better."

Those rules could be dismissed as an expression of romantic nostalgia, but I think they reflect an intuitive grasp of something deeper and timeless about places and people.

Thomas Kinkade seems to understand that places - houses and shops, landscapes and streetscapes - have the ability to touch the heart. In his choice of subjects and his depiction of main streets, neighborhoods, country cottages, townhouses, and bungalows, he strikes a chord with the viewer.

His cinematic suggestions brought to mind what architect Christopher Alexander called the "Timeless Way of Building."

This timeless way expresses itself in patterns in the way we make a town or a building.

Every building, neighborhood, town, and city is constructed from a collection of patterns. Alexander observed that some patterns are living and some are dead. The ones that are living are those that connect in some way with human nature - they attract people, making them feel at home and alive.

Dead patterns repel people, making them feel ill at ease and restless. A place shaped by dead patterns becomes neglected and uncared for and attracts trash, decay, and crime.

In the book A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction, Alexander and his colleagues identified and gave names to 253 lively patterns that appear to be timeless, recurring across cultures and centuries. Kinkade's suggestions to his filmmakers echo many of these patterns: Pools of Light, Magic of the City, Four-Story Limit, Paths and Goals, Warm Colors, Street Windows, Shielded Parking.

(The list of patterns, with brief descriptions, is online at http://downlode.org/Etext/Patterns/) UPDATE 2021/07/13: That link is dead, but you can find a list of patterns (sans descriptions) on Christopher Alexander's Pattern Language website, with descriptions and examples available to paying subscribers.

Those same living patterns are evident in Kinkade's paintings.

Kinkade's cottages are perhaps his best known images, but he's produced nearly as many cityscapes. Some depict the busy streets of San Francisco (a favorite subject of his), Paris, Kansas City, Charleston, and Chicago. Others show the slower pace on the main streets of resort towns like Key West, Mackinac Island, and Carmel. Some of the paintings feature landmarks, but most are ordinary street scenes.

Although his work may be sold in suburban malls to be hung on suburban walls, the realities of suburban life do not intrude onto Kinkade's canvas.

In Kinkade's cityscapes, the townhouses and commercial buildings come up to the sidewalks and have windows that allow passersby to see inside. In his neighborhood scenes, the houses have porches and big windows facing the street.

The buildings have eye-catching details above the windows and along the rooflines. The scale of the buildings and the details are proportionate to the pedestrians passing by. The light is gentle, coming through building windows, from small lights reflecting on the façade or signage, or from subdued streetlights.

In Kinkade's world, there are no glaring "acorn" streetlights blinding the viewer from seeing anything else. There are no surface parking lots, blank walls, or mirrored glass surfaces. I have looked through Kinkade's collection and can't find a single painting of a McMansion or a Garage Mahal.

Try to imagine a Kinkade-style painting of a snout house - the sort where the garage is the most prominent feature of the home, sticking out toward the street. There wouldn't be any windows for his trademark warm light to shine out of. It wouldn't work, and it wouldn't sell.

But I could imagine him painting the Charles Dilbeck-designed home at 19th and Peoria - with the snow on the peaked Tudor-style roof and diagonally-paned vertical windows framing a glowing Christmas tree within.

I could imagine a successful Kinkade painting of Cherry Street, but not one of 71st Street.

Kinkade's paintings sell because they depict places where people want to be, places that are full of life.